What is TV Tropes?

TV Tropes (https://tvtropes.org/) is an online wiki that catalogs and analyzes “tropes”, the recurring narrative devices, patterns, or conventions found in various media, including video games, films, TV shows, books, and comics. Launched in 2004, it started with a focus on television but now covers all forms of fiction. Users contribute to create a dynamic database of tropes with examples and explanations.

What is a “Trope”?

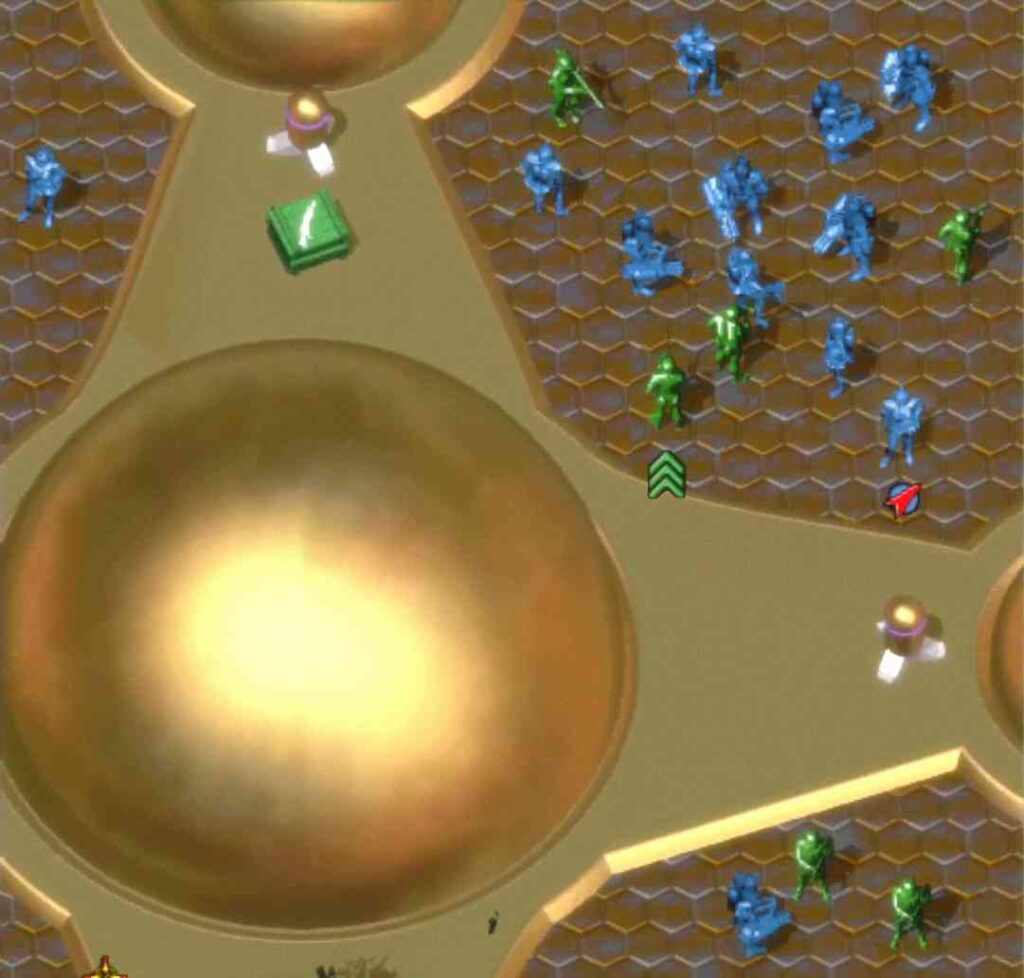

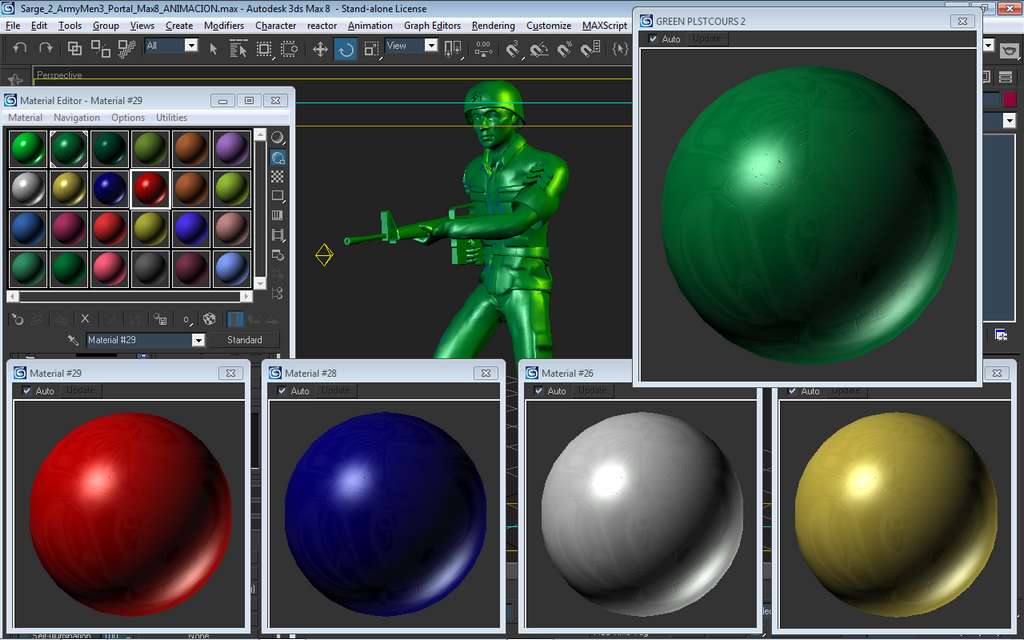

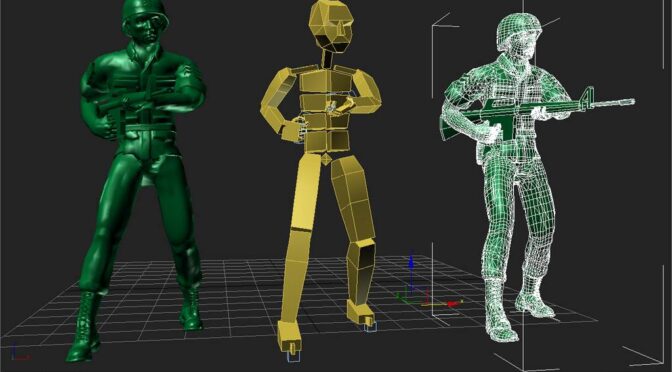

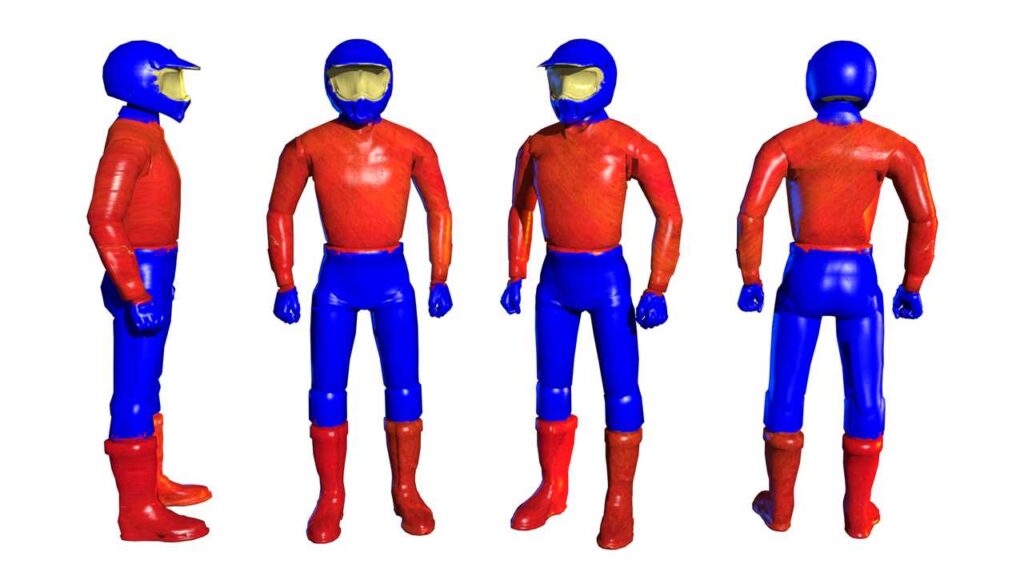

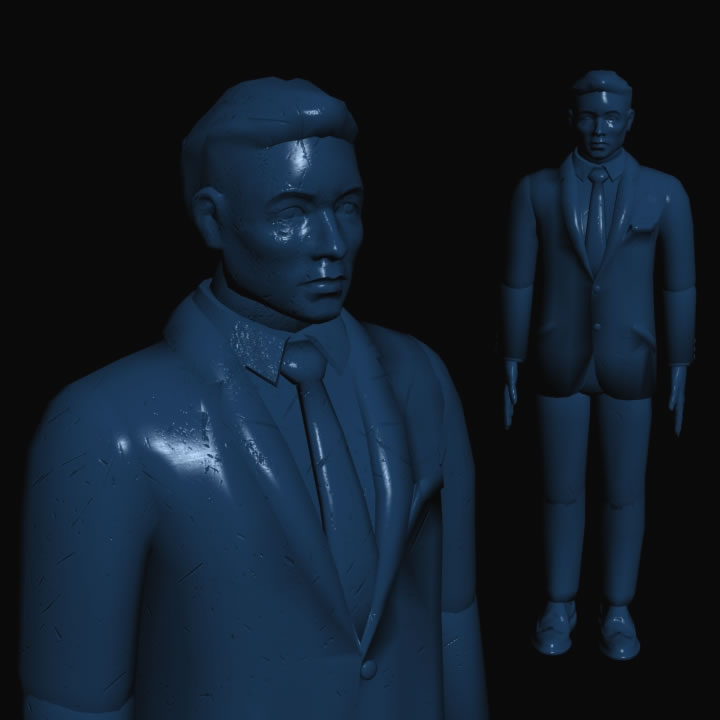

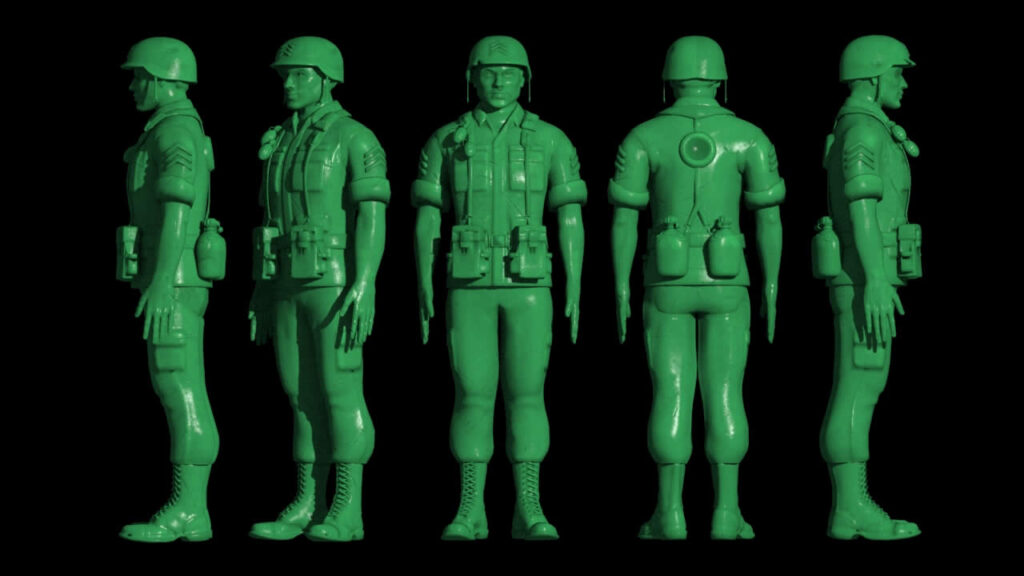

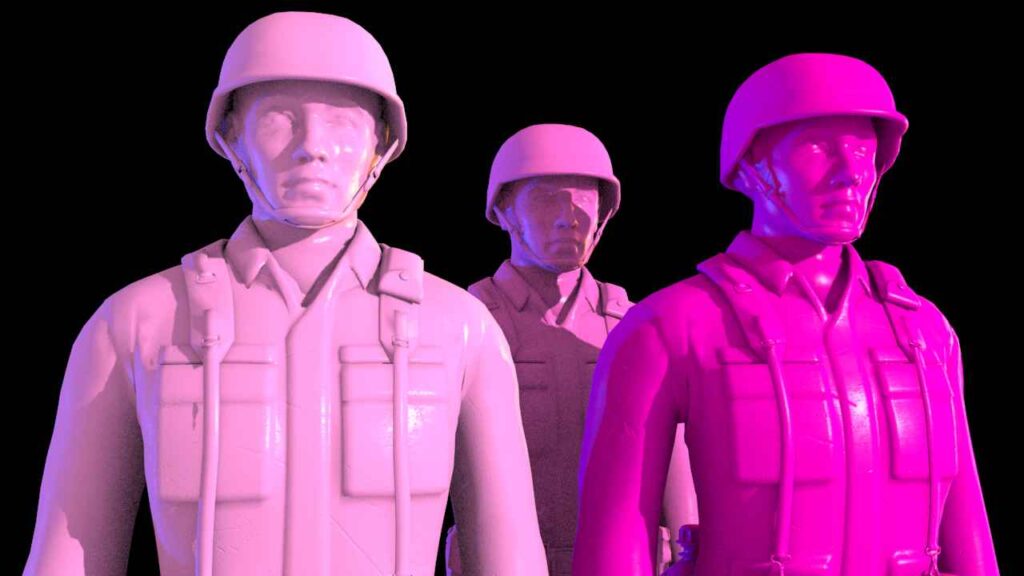

A trope is a storytelling tool, like a cliché or pattern, used to convey ideas or structure narratives. Examples include the “Reluctant Hero” or “Evil Overlord.” TV Tropes documents these, showing how they appear across media, such as “Color Identified Factions” in *Army Men*, where factions are defined by colors like Green (good) and Tan (evil).

Purpose and Use

TV Tropes helps fans, writers, and creators understand narrative structures by breaking down stories into their building blocks. It’s a resource for analyzing how tropes are used or subverted and inspires creative storytelling. For this *Army Men* project, it provides detailed trope lists that can be considered when shaping the Toyverse.

Cultural Impact

Popular among fans and narrative enthusiasts, TV Tropes is known for its engaging, sometimes humorous style and interconnected structure, often leading users down a “rabbit hole” of related tropes. It’s a valuable tool for studying storytelling patterns and ensuring unique content creation.

This series has examples of:

-

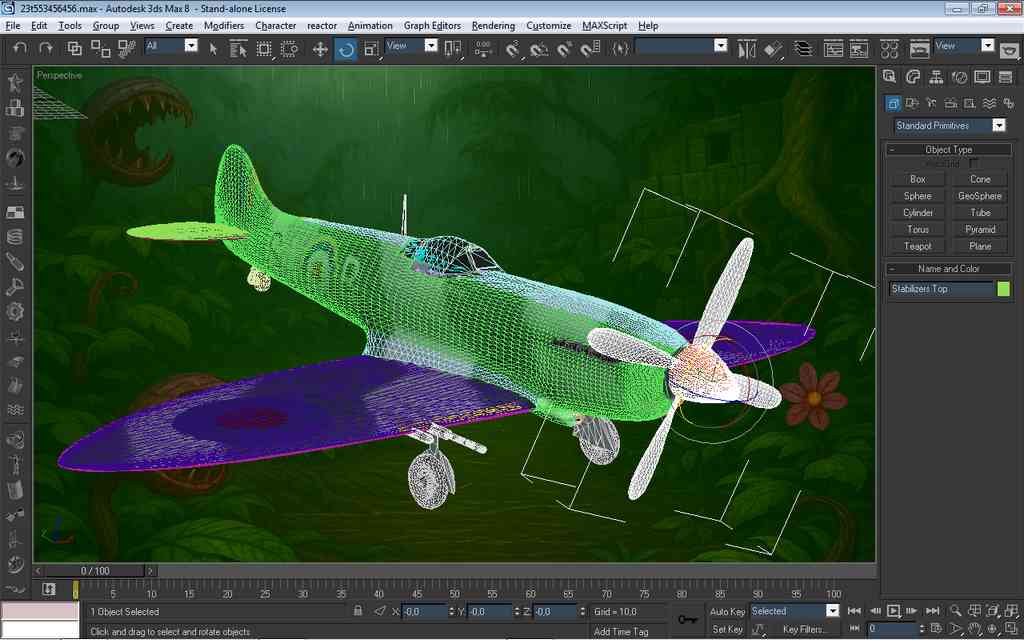

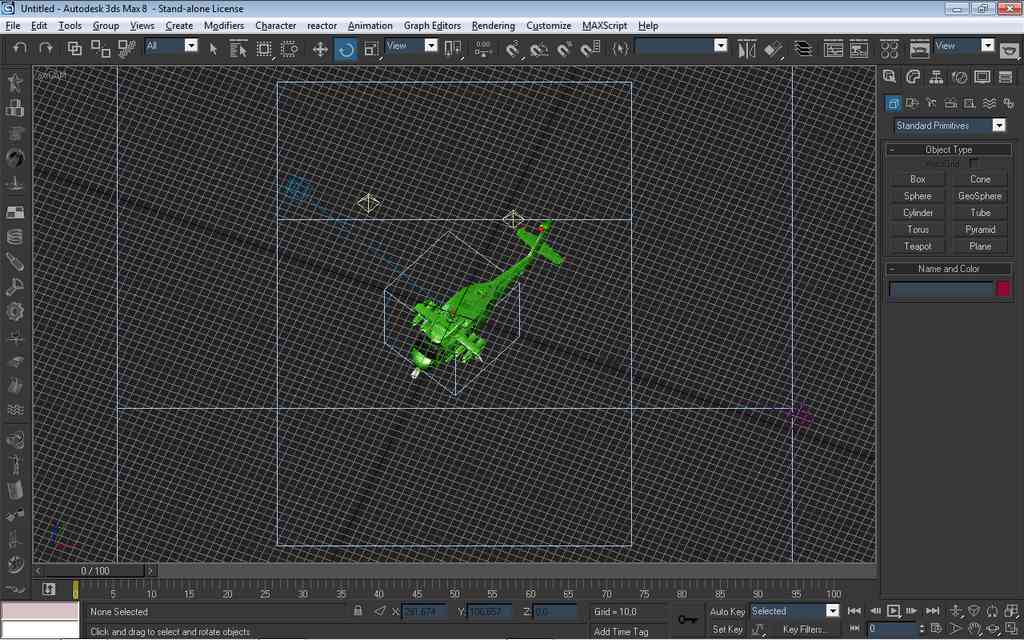

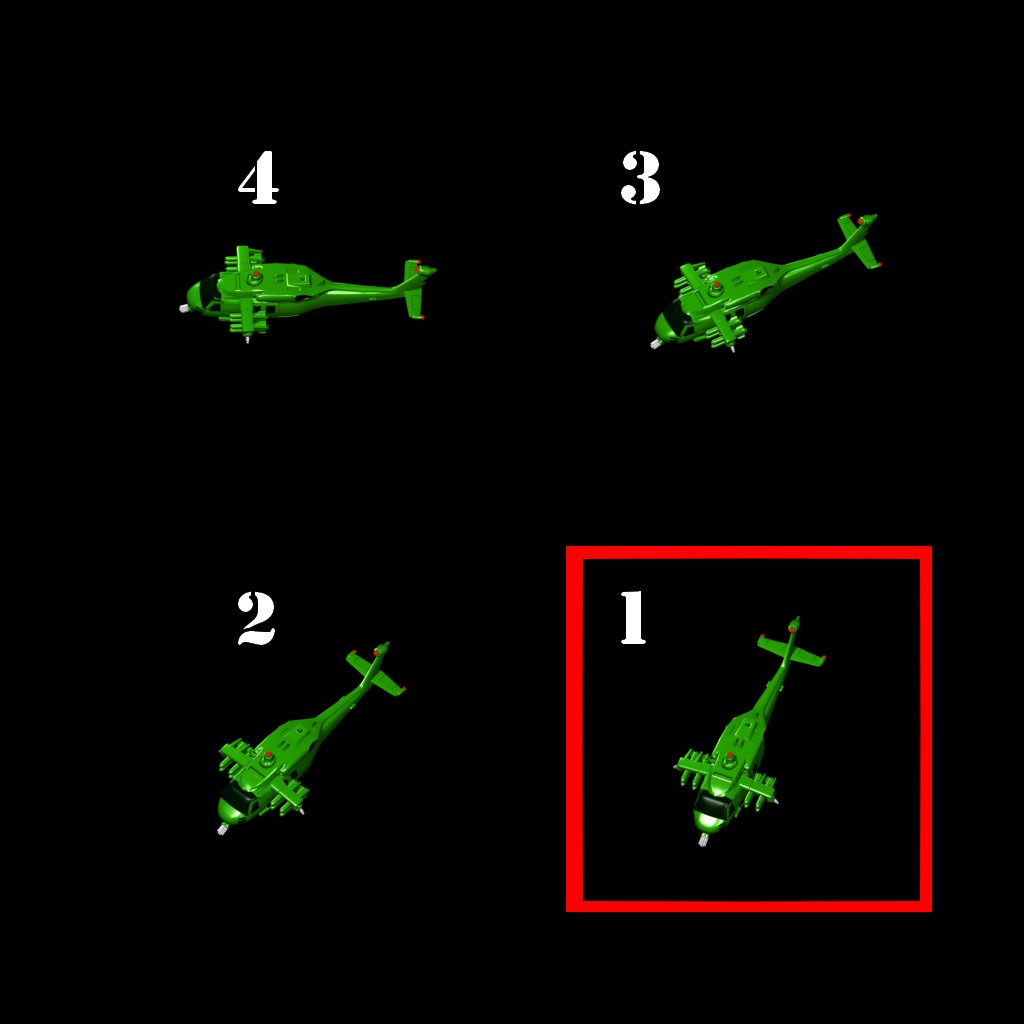

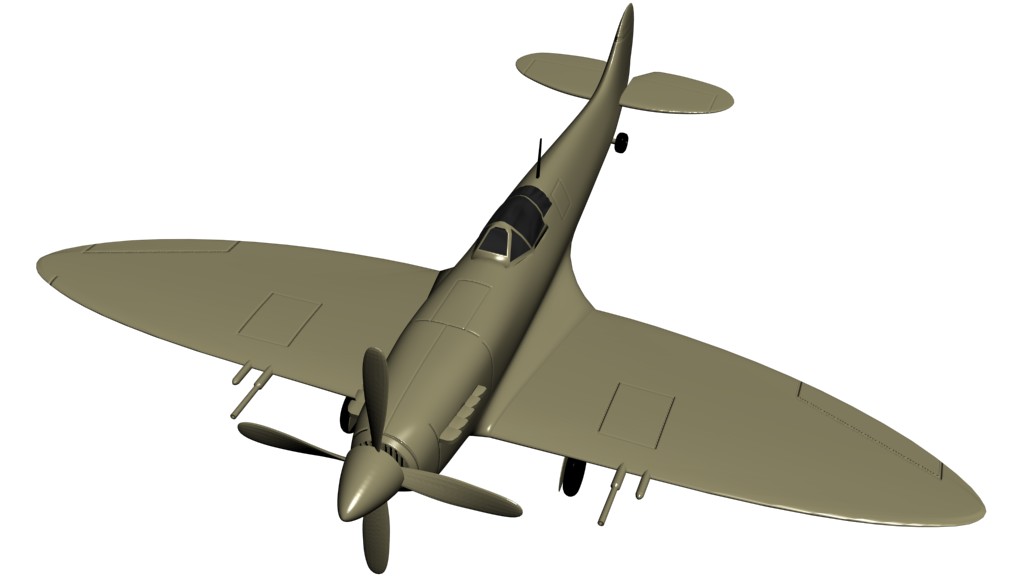

- Skilled Aviator: Captain William Blade. He’s basically the commander of the entire Green Army air force.

- Increased Action Sequel:

- Army Men was a real-time tactics shooter in an isometric view, that often saw you having to plan your next move carefully, as some areas were so fraught with enemy soldiers venturing into them would be suicide. The next game lessened the need for this, as little things, like having to account for soldiers hearing incoming mortars was removed, and rarely was it not beneficial to clear a map of enemies. Before long, the series shifted into a third-person shooter.

- Zig-zagged regarding the third person shooter games. The “World War” series leans on the tactical side, with Team Assault in particular dramatically reduce soldier’s health, both you and your enemies side, while Sarge Heroes is often about charging, shooting, and dodging as lone soldier Sergeant Hawk, and Air Assault features a single helicopter force as the protagonist.

- Spotlight Moment:

- The Game Boy Color port of Sarge’s Heroes 2 (which functions as a completely different game compared to the console versions), Riff, Scorch and Vikki are the only playable characters, and they even have their own personal vehicles to ride.

- Hoover also has a level dedicated to himself in Army Men RTS where he proves to be actually pretty good at leading a team.

- Friendly Villain: General Plastro. He may be the bad guy, but at least he’s honest enough to admit it, as well as to compliment the enemy when they do well. This is best shown in the opening cutscene for the final level of Sarge’s Heroes, where he and several Tan troops get the drop on an empty-handed Sarge, only for Sarge to take out the troops by kicking a block at them. Plastro genuinely compliments and congratulates Sarge on his cleverness, admitting he didn’t even see it coming; however, when Sarge asks why Plastro doesn’t drop the gun and fight him one-on-one, Plastro straight up tells Sarge it’s “because I’m the bad guy.”

- Spray Can Fire Thrower: An aerosol is one of the weapons you can get in the second game.

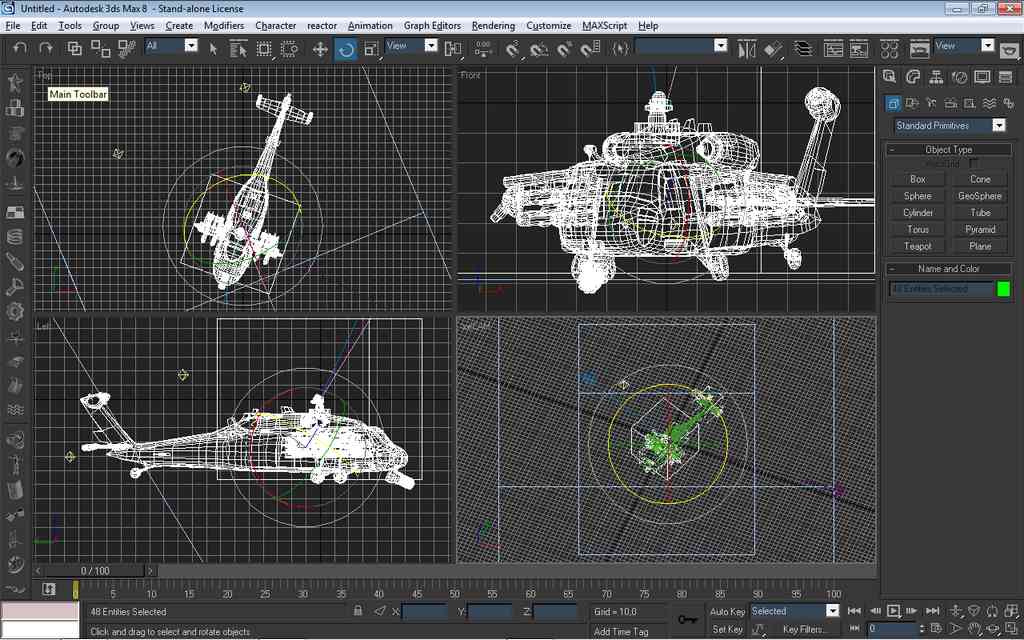

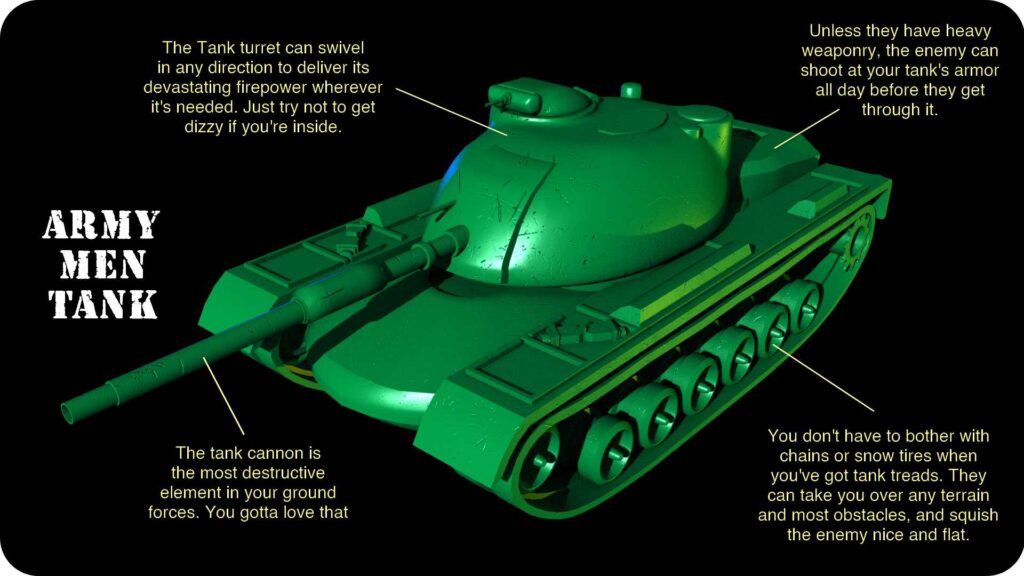

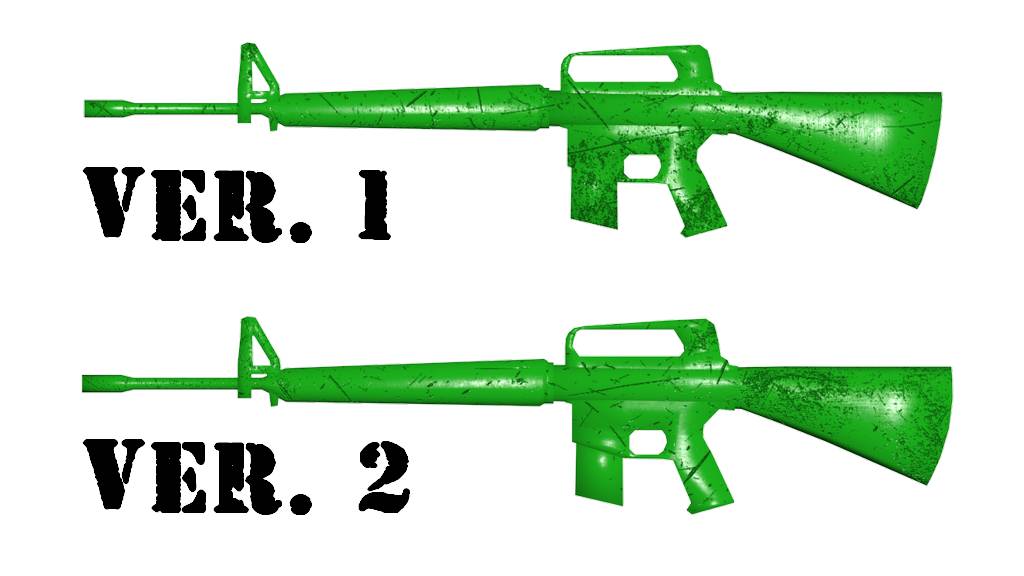

- Time Period Mishmash: The game’s weapons and vehicles are a combination of those from World War II and The Vietnam War. For instance, the standard rifle is based on the M16 and the standard tank is based on the M48 Patton, both from the Vietnam War era, alongside Huey helicopters. However, there are also propeller fighter planes, half-tracks, and mass paratrooper drops that were either not used or phased out by the Vietnam War.

- End of World Record: The Colonel’s final report before losing contact in Sector C-4 in the second game.

- Cool but Inefficient: Hero Units in RTS. They do more damage than their normal counterparts and can usually take more punishment than them, but the lack of healing means that you need to be careful in how you use them, lest you lose out on a strong unit for the rest of the mission.

- Tough Team: Bravo Company is apparently feared by the Tan army. In Green Rogue, the mere information that Bravo is going to be out of action for several weeks recovering from surgery is enough for the Tan to decide to launch an all out assault against Green positions, reasoning that Bravo was literally the only thing that could have stopped them.

- Terrible Leader: Plastro, from punching out underlings that bring him bad news to actively plotting betrayal against allies for little reason other than that’s what bad guys like him do.

- Villain Victory: Malice gets what he wanted in the end, to make Sarge suffer and destroy everything and everyone that he valued. The only mitigation is that Sarge is able to take revenge and, by the time it is all over, ultimately seems to regard Gooding with more pity than anger.

- Main Antagonist: General Plastro for most of the series. Unless noted below, Plastro is often the overarching villain who is also never directly fought.

- Major Mylar for Army Men 2.

- The alien leader in Toys in Space.

- Colonel Blintz in the RTS game.

- Lord Malice in Sarge’s War.

- Major Malfunction in the game of the same name.

- Witty Post-Kill Remark: Blowing up tents in one level in Army Men 3D will cause Sarge to quip “Knock knock.”

- Infinite Ammo: Most of the games tend to give your starting weapon infinite ammo, sometimes with a drawback (the M16 in the N64 Sarge’s Heroes games has a very slow rate of fire, the PS1 Sarge’s Heroes 2 makes it overheat when fired too much) and sometimes with an ammo-guzzling upgrade available (the BAR in the original two games, which trades the infinite ammo for a much higher rate of fire).

- Scare-Induced Incontinence:

- Implied with Hoover immediately after regrouping with him in Sarge’s Heroes:

Col. Grimm: Do you think he can make it back to the landing pad on his own?

Sarge: That’s a negative sir; moisture is imminent.

Hoover: Aw, geeze!

- A “You Lose” scene in Toys In Space depicts a Green soldier surrounded by Tan troops laughing at him while dropping his weapon and wetting himself.

- Reinforcements Arrival: Air cavalry, to be exact. This is the role that Capt. Blade’s squad plays. He even wears an old cavalry hat.

- Proud Evildoer: Plastro, especially in Sarge’s Heroes, knows he’s the bad guy, and he wouldn’t have it any other way. Lampshaded all throughout.

Sarge: Plastro! Why don’t you drop that gun and face me like a man?

Plastro: Because I’m the bad guy, that’s why!

…

Plastro: Burn it all, starting with [Bridgette’s] blasted Blue homeland.

Vikki: Plastro! How could you?

Plastro: Well, somebody’s not paying attention. I’m the bad guy!

-

- Important Later Character: In Sarge’s War, Major Gooding, who is mentioned all of one time before the reveal.

- Prove Innocence: Blade is forced to do this, after the actions under pretend traitor, and does it by delivering much needed supplies to besieged Green forces, and helping either Sarge or Vikki take out a Tan base.

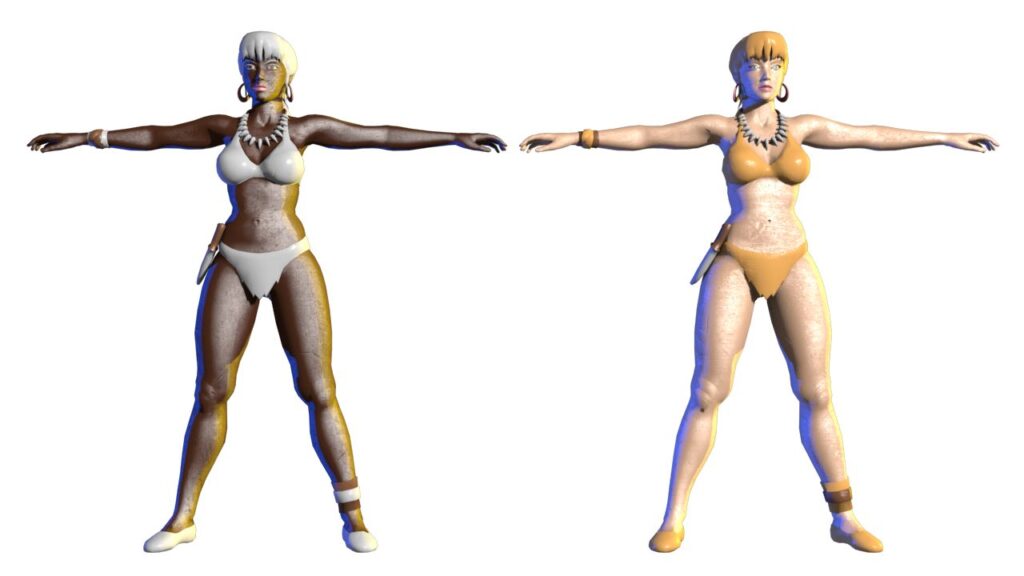

- Possessive Jealous Female: Bombshell really doesn’t like it when Capt. Blade flirts with Vikki.

- Icy Marksman: Bullseye, the Bravo Company sniper introduced in RTS. He’s even called the ice man in the game’s manual.

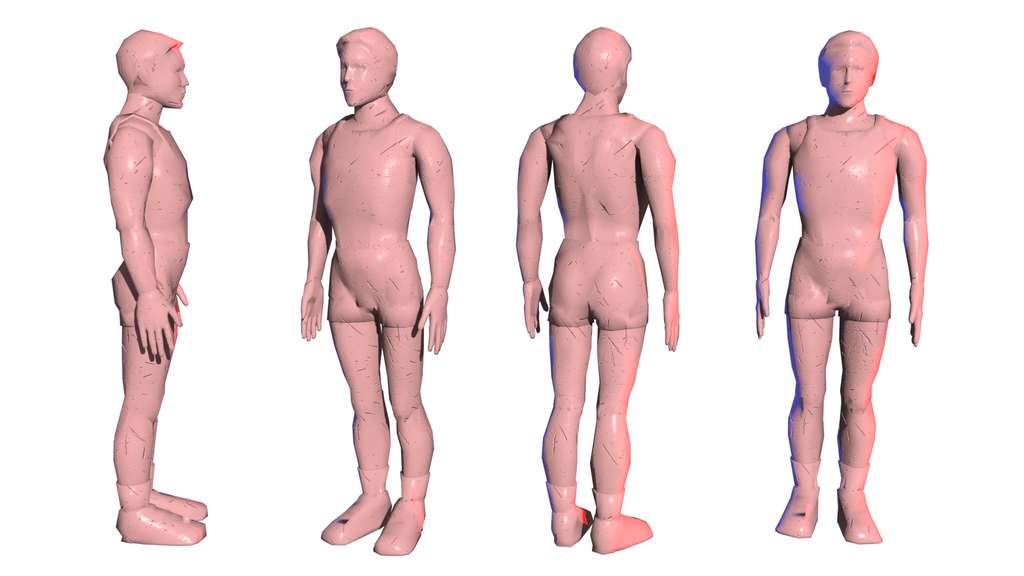

- Color Identified Factions: Every faction across the series. The four most common are Green being good guys, Tan being evil, Gray being, well, gray (in some games they’re allied with the Greens, in others they’re against everyone), and Blue being spies, typically allied with the Tans.

- Resource Management System: Army Men RTS, natch.

- Story Restart:

- The last two games, Major Malfunction and Soldiers of Misfortune, have an all new plot and characters.

- Sarge’s Heroes was a lesser case – it’s still the same setting, with the same war and even the same bad guy, but all of the other characters were newly-introduced; even Plastro had his characterization played up more compared to the slightly more serious villain he was in the original two games.

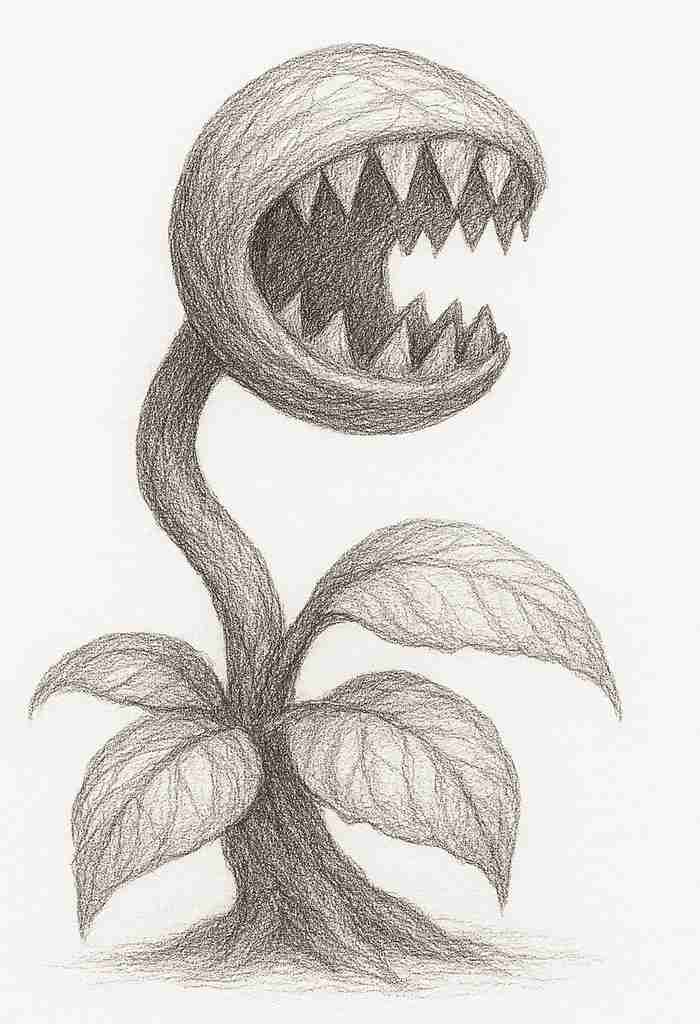

- Scary Roaches: Starting with Army Men II, they start appearing in the real world. Due to the limited graphics of the PlayStation games, they can be downright horrifying.

- Grimmer and Harsher:

- Sarge’s War, to a large extent. Sometimes borders on parody of the gritty war hero type film.

- Before that were the World War games, which played war is hell devastatingly straight.

- Dry Wit Commentator: Sarge in the Sarge’s Heroes games, when he isn’t being a dutiful soldier. Captain Blade meanwhile is in snark mode 24/7.

- Aerial Attack: One of the power-ups invoked from time to time.

Sarge: This is Sarge, I need an air strike, over.

- Programmer Prediction: In the mission where Capt. Blade has to pick up a squad led by either Sarge or Vikki to blow up a radar station, picking Vikki while Bombshell is your co-pilot causes her to get really jealous, to the point she will actually ask you to pick Sarge.

- Craven Traitor:

- Hoover, the team’s minesweeper, looks like he wished he called himself a conscientious objector, and will retreat in RTS if he takes even a little damage.

- Though Plastro has his moments of villainous bravery, suicidal or otherwise, when he’s captured at the end of Sarge’s Heroes 2 and Sarge threatens to punch his lights out, his reaction is to shout “not the face!” and immediately faint.

- Depressing Conclusion: Army Men: Sarge’s War is pretty much this for the whole series. Bravo Company, Grimm and Vikki are melted, Lord Malice was Major Gooding all along, and Sarge feels empty inside after killing him.

- Sudden Death Offscreen: Them, if you may. The aforementioned Sarge’s War has every named character and series mainstay since Sarge’s Heroes, except for Sarge himself, killed off by an explosion hidden in a peace monument orchestrated by Lord Malice, the new villain.

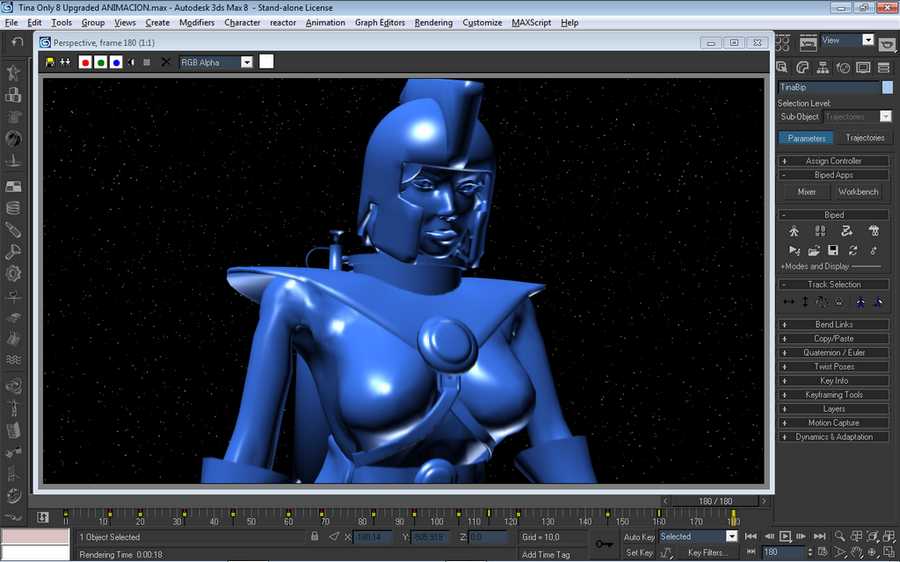

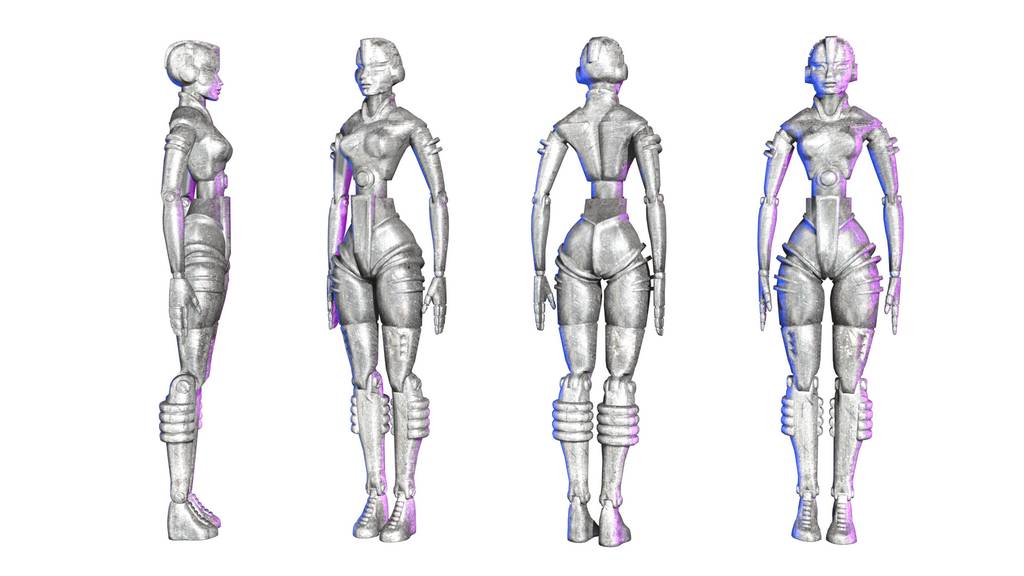

- Bland Reaction: Tina Tomorrow is not the most expressive person.

- Last Words of Affection: Vikki’s last words to Sarge in Sarge’s War.

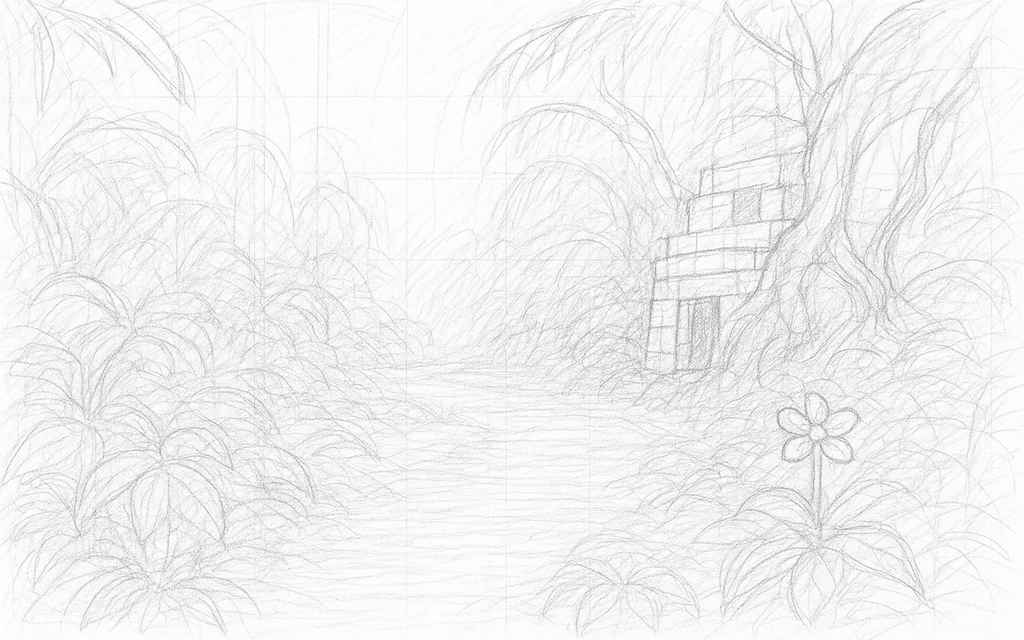

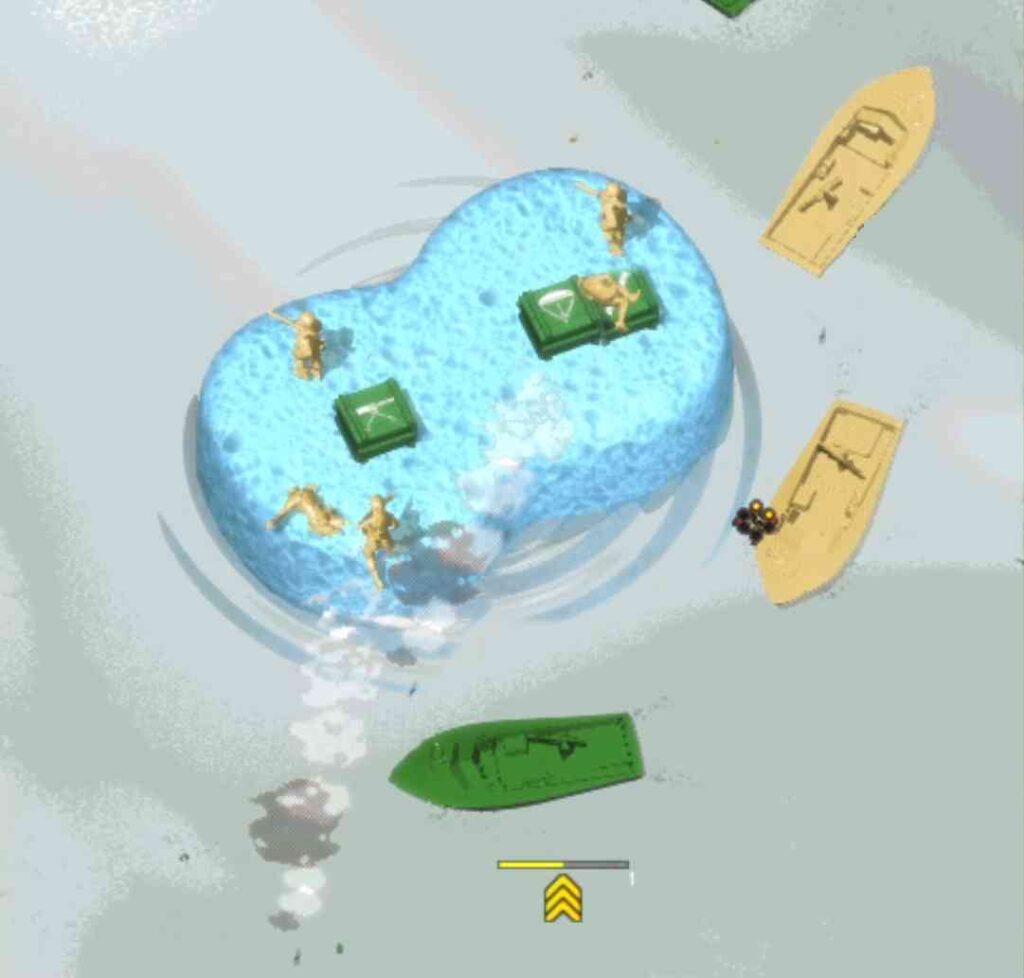

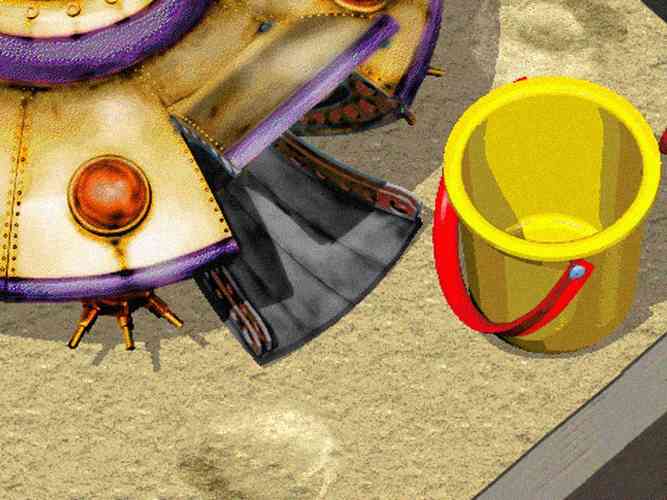

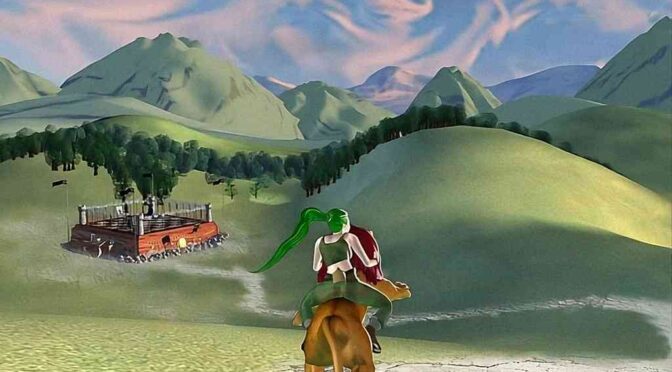

- Initial Entry Oddities: The first game lean towards a top-down tactical shooter where your soldiers can easily die. Furthermore, the tone is more sombre and the plot is minimal, and the sequel hook ending where your soldiers enter the real world is treated as a surprise. The second game took the “toy soldiers fighting in the real world” plot and ran, becoming a denser and wackier increased action sequel as the soldiers fight other toys and insects over kitchen counters and gardens.

- Laser Armament: The aliens in Toys In Space use them. Sarge can even find a laser rifle, an upgrade to the auto-rifle and Vulcan gun.

- Protect Task: These have been around since the first game, they range from barely an escort (being able to just order your men to hold while you kill everything along the way and/or the VIP being almost as badass as Sarge) to almost controller-breaking frustrating.

- Villainous Cackle: Plastro is a fan of this, even when so badly injured from being used as a literal chew toy, twice, that he can’t stop coughing every time he tries.

- Hero to Villain Switch:

- Colonel Blintz in the RTS after quite literally losing his mind.

- Major Gooding in Sarge’s War. He becomes Lord Malice after a mission where he is nearly killed and blames Sarge for leaving him behind, although Sarge couldn’t have known he was still alive given the amount of damage he took.

- Alignment Flip-Flop: Bridgette Blue, and all of the blue nation really. They’ll work for whoever pays best, whoever isn’t trying to kill them, or even whoever currently suits their own agenda.

- Imaginary Equivalent Society:

- The Green Nation is Type I or “The Great” Eagleland.

- The Tan Nation is a combination of common media belligerents such as World War II Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, or Ba’athist Iraq, complete with something of a mix of Saddam Hussein (the face) and Fidel Castro (the name and build) as their leader General Plastro.

- The Blue Nation is an analogue of the various French sides in WWII that works out as a villainous version of cheese-eating surrender monkeys – they have an extensive spy network, but they also work with the Nazi Germany analogue and are very quick to surrender.

- The Gray Nation, in turn, ends up as a heroic version of the Vietcong, essentially North Vietnam’s guerrilla warfare expertise (usually) combined with the South’s loyalty to the USA analogue.

- Pretend Traitor:

- Captain Blade spends half of Air Attack 2 on the run, after being court-martialed and then breaking out of prison for his actions almost getting his wingmen killed.

- Vikki pulls this briefly in Sarge’s Heroes after getting captured, as part of a honey trap.

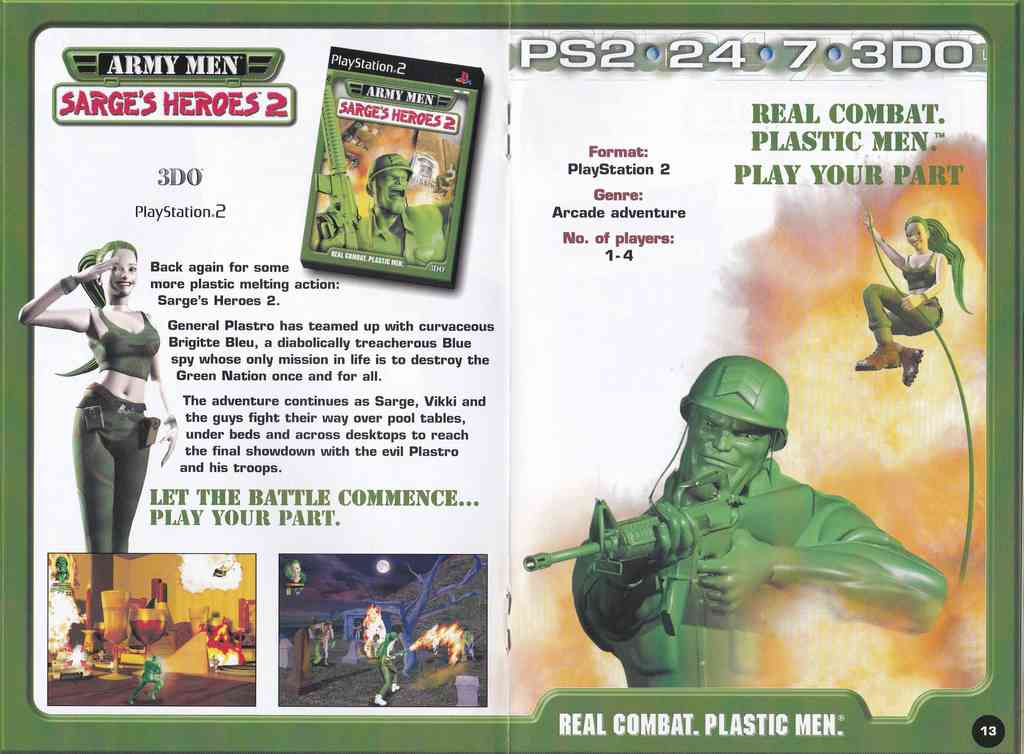

- Bridgette Bleu is revealed to be this in Sarge’s Heroes 2.

(Note: This modified version is based on the original content from the link below, with trope names rephrased and order slightly adjusted for originality while preserving all original information, quotes, and details intact. Please, consider check the original link below)